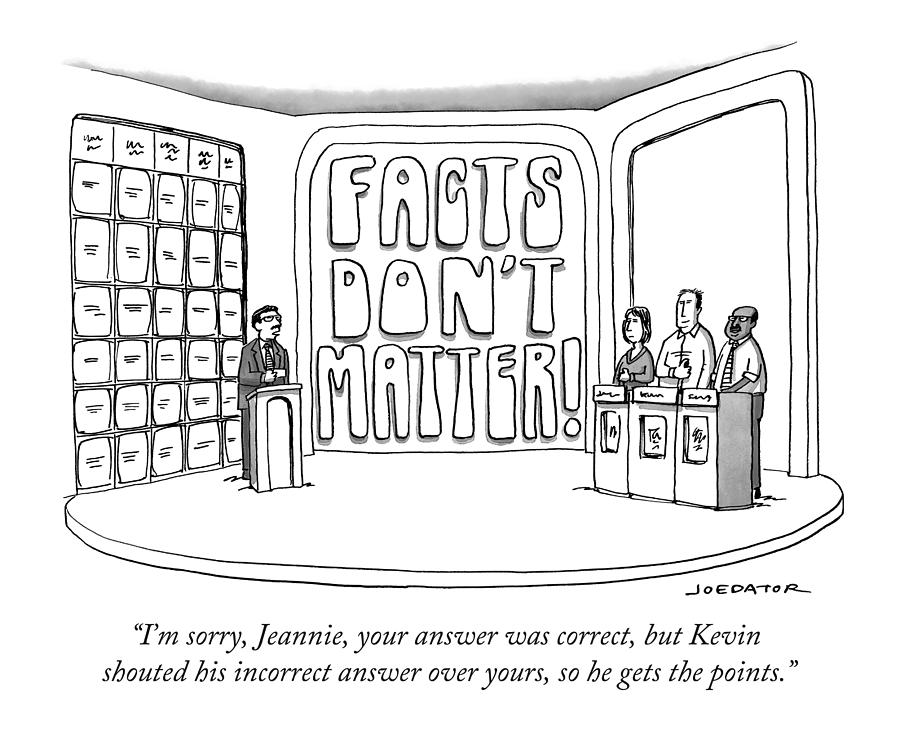

As the competition for our attention has gotten more cutthroat, so has the narrativization of everything. In the war for clicks and pageviews, the content with the most dumbed-down, most easily digestible point of view wins. It’s so tempting to glance through the headlines and consider yourself informed.

Stories are decisions. There’s no such thing as “the story,” no pre-existing idea or self-determined material that belongs in “the story” by necessity of its chosen subject or characters. It’s all invented by people with agendas and worldviews that differ from your own.

Complex problems require complex solutions. And almost all problems are complex ones. News shows and media outlets would have us believe differently. By shaping the news into simple narratives, for-profit organizations are able to give our brains what they crave: a sense of understanding. Since our brains don’t like randomness, we are constantly looking at sequences of events and weaving our own, or other’s explanations into them.

We believe that our opinions are the result of years of rational, objective analysis. But we suffer from biases formed from the result of years of paying attention to information which confirms what we believe while ignoring information that challenges our preconceived notions. Once we have formed a view, we embrace information that confirms that view while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt on it.

The truth is, anything that captures our attention — from a stone lying on the side of a road to the latest supreme court ruling — contains a captivating world beneath the superficial labels that we apply to them. The word “know” is incredibly deceptive.

“When you don’t cover up the world with words and labels, a sense of the miraculous returns to your life that was lost a long time ago when humanity, instead of using thought, became possessed by thought.” ― Eckhart Tolle, A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose

Our ignorance can feel overwhelming as explained by John Salvatier in his post, Reality has a surprising amount of detail:

“Before you’ve noticed important details they are, of course, basically invisible. It’s hard to put your attention on them because you don’t even know what you’re looking for. But after you see them they quickly become so integrated into your intuitive models of the world that they become essentially transparent.

This means it’s really easy to get stuck. Stuck in your current way of seeing and thinking about things. Frames are made out of the details that seem important to you. The important details you haven’t noticed are invisible to you, and the details you have noticed seem completely obvious and you see right through them. This all makes makes it difficult to imagine how you could be missing something important.”

So how do we overcome these deceptive narratives? Step one: admit you have a problem. Ask yourself, “who wins?” Does the conclusion you’ve come to in support of placing yourself above others? If so, there’s a chance you’re not seeing the whole picture.

As the wise Andrew WK says,

“When we anticipate with ferocious glee the next chance we have to prove someone “wrong” and ourselves “right,” all the while disregarding the vast complexity of almost every subject — not to mention the universe as a whole — we are reducing the beauty and magic of life to a “side” or a “type,” or worst of all, an “answer.” This is the power of politics at it’s most sinister.”

Step two: exercise your critical thinking muscles. You need to constantly remind yourself that there is always more to the story.

A steady diet of filter bubble, outrage-clickbait that is compulsively consumed in tiny doses on a small screen while being distracted by flashing alerts, likes, badges and breaking news won’t help — in fact, that kind of consumption will only strengthen the brain muscles that encourage shallow thinking.

Attack the deep details of subjects to see the multiple facets being explored, the reasoning used by the other side and ask child-like simple questions that’ll lay bare the incredible complexity of everything.